Probability Fundamentals

Lecture 03

January 29, 2025

Review

Null Hypothesis Significance Testing

- Binary “significant”/“non-significant” decision framework;

- Accept or reject null hypothesis \(\mathcal{H}_0\) based on p-value of test statistic (relative to significance level \(\alpha\));

- “Typical” statistical models for \(\mathcal{H}_0\) often chosen out of computational convenience

- There be dragons: Multiple comparisons, lack of statistical power, reading rejection of \(\mathcal{H}_0\) as acceptance of alternative \(\mathcal{H}\)

What NHST Means (and Doesn’t)

- Rejection of \(\mathcal{H}_0\) does not mean \(\mathcal{H}\) is true

- Not rejecting \(\mathcal{H}_0\) does not mean \(\mathcal{H}\) is false.

- Says nothing about \(p(\mathcal{H}_0 | y)\)

- “Simply” a measure of surprise at seeing data under null model.

Probability “Review”

What is Uncertainty?

…A departure from the (unachievable) ideal of complete determinism…

— Walker et al. (2003)

Types of Uncertainty

| Uncertainty Type | Source | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Aleatory uncertainty | Randomness | Dice rolls, Instrument imprecision |

| Epistemic uncertainty | Lack of knowledge | Climate sensitivity, Premier League champion |

Probability

Probability is a language for expressing uncertainty.

The axioms of probability are straightforward:

- \(\mathcal{P}(E) \geq 0\);

- \(\mathcal{P}(\Omega) = 1\);

- \(\mathcal{P}(\cup_{i=1}^\infty E_i) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty \mathcal{P}(E_i)\) for disjoint \(E_i\).

Frequentist vs Bayesian Probability

Frequentist:

- Probability as frequency over repeated observations.

- Data are random, but parameters are not.

- How consistent are estimates for different data?

Bayesian:

- Probability as degree of belief/betting odds.

- Data and parameters are random variables;

- Emphasis on conditional probability.

But What, Like, Is Probability?

Frequentist vs. Bayesian: different interpretations with some different methods and formalisms.

We will freely borrow from each school depending on the purpose and goal of an analysis.

Probability Distributions

Distributions are mathematical representations of probabilities over a range of possible outcomes.

\[x \to \mathbb{P}_{\color{green}\mathcal{D}}[x] = p_{\color{green}\mathcal{D}}\left(x | {\color{purple}\theta}\right)\]

- \({\color{green}\mathcal{D}}\): probability distribution (often implicit);

- \({\color{purple}\theta}\): distribution parameters

Sampling Notation

To write \(x\) is sampled from \(\mathcal{D}(\theta) = p(x|\theta)\): \[x \sim \mathcal{D}(\theta)\]

For example, for a normal distribution: \[x \overset{\text{i.i.d.}}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma)\]

Probability Density Function

A continuous distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) has a probability density function (PDF) \(f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \theta)\).

The probability of \(x\) occurring in an interval \((a, b)\) is \[\mathbb{P}[a \leq x \leq b] = \int_a^b f_\mathcal{D}(x)dx.\]

Important: \(\mathbb{P}(x = x^*)\) is zero!

Probability Mass Functions

Discrete distributions have probability mass functions (PMFs) which are defined at point values, e.g. \(p(x = x^*) \neq 0\).

Cumulative Density Functions

If \(\mathcal{D}\) is a distribution with PDF \(f_\mathcal{D}(x)\), the cumulative density function (CDF) of \(\mathcal{D}\) is \(F_\mathcal{D}(x)\):

\[F_\mathcal{D}(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_\mathcal{D}(u)du.\]

Relationship Between PDFs and CDFs

Since \[F_\mathcal{D}(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_\mathcal{D}(u)du,\]

if \(f_\mathcal{D}\) is continuous at \(x\), the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus gives: \[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = \frac{d}{dx}F_\mathcal{D}(x).\]

Quantiles

The quantile function is the inverse of the CDF:

\[q(\alpha) = F^{-1}_\mathcal{D}(\alpha)\]

So \[x_0 = q(\alpha) \iff \mathbb{P}_\mathcal{D}(X < x_0) = \alpha.\]

Selecting a Distribution

Distributions Are Assumptions

Specifying a distribution is making an assumption about observations and any applicable constraints.

Examples: If your observations are…

- Continuous and fat-tailed? Cauchy distribution

- Continuous and bounded? Beta distribution

- Sums of positive random variables? Gamma or Normal distribution.

Why Use a Normal Distribution?

Two main reasons to use linear models/normal distributions:

- Inferential: “Least informative” distribution assuming knowledge of just mean and variance;

- Generative: Central Limit Theorem (summed fluctuations are asymptotically normal)

Source: r/GymMemes

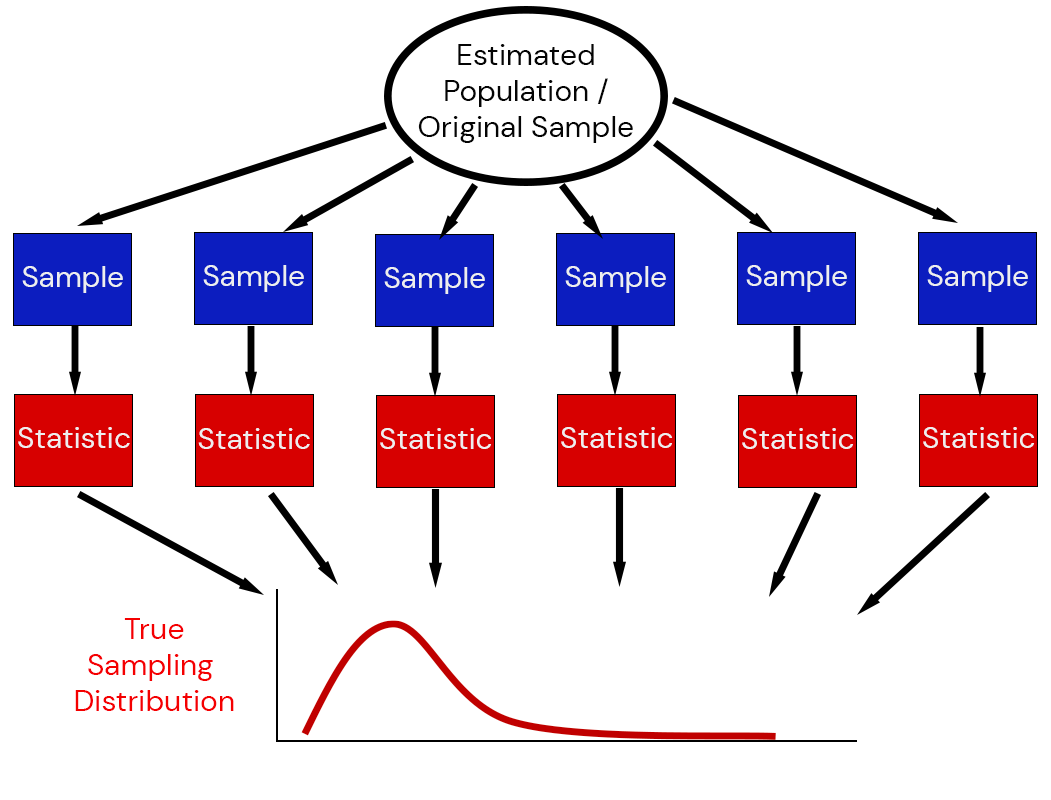

Statistics of Random Variables are Random Variables

The sum or mean of a random sample is itself a random variable:

\[\bar{X}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \sim \mathcal{D}_n\]

\(\mathcal{D}_n\): The sampling distribution of the mean (or sum, or other estimate of interest).

Sampling Distributions

Illustration of the Sampling Distribution

Central Limit Theorem

If

- \(\mathbb{E}[X_i] = \mu\)

- and \(\text{Var}(X_i) = \sigma^2 < \infty\),

\[\begin{align*} &\bbox[yellow, 10px, border:5px solid red] {\lim_{n \to \infty} \sqrt{n}(\bar{X}_n - \mu ) = \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)} \\ \Rightarrow &\bbox[yellow, 10px, border:5px solid red] {\bar{X}_n \overset{\text{approx}}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2/n)} \end{align*}\]

Central Limit Theorem (More Intuitive)

For a large enough set of samples, the sampling distribution of a sum or mean of random variables is approximately a normal distribution, even if the random variables themselves are not.

Source: Unknown

“What Distribution Should I Use?”

There is no right answer to this, no matter what a statistical test tells you.

- What assumptions are justifiable from theory?

- What information do you have?

“What Distribution Should I Use?”

For example, suppose our data are counts of events:

- If you know something about rates, you can use a Poisson distribution

- If you know something about probabilities, you can use a Binomial distribution.

Q-Q Plots

One exploratory method to see if your data is reasonably described by a theoretical distribution is a Q-Q plot.

Fat-Tailed Data and Q-Q Plots

Maximum Likelihood

Likelihood

How do we “fit” distributions to a dataset?

Likelihood of data to have come from distribution \(f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)\):

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x}) = \underbrace{f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)}_{\text{PDF}}\]

Normal Distribution PDF

\[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}^2\right)\right)\]

Likelihood of Multiple Samples

For multiple (independent) samples \(\mathbf{x} = \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}\):

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x}) = \prod_{i=1}^n \mathcal{L}(\theta | x_i).\]

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 1.9e-8 |

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 1.9e-8 |

| \(N(-1, 2)\) | 1.5e-8 |

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 1.9e-8 |

| \(N(-1, 2)\) | 1.5e-8 |

| \(N(-1, 1)\) | 4.6e-8 |

Maximizing Likelihood

To find the parameters \(\hat{\theta}\) which best fit the data:

\(\hat{\theta} = \max_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x})\)

Generally Maximizing Likelihood

Can use optimization algorithms to maximize \(\theta \to \mathcal{L}(\theta | x).\)

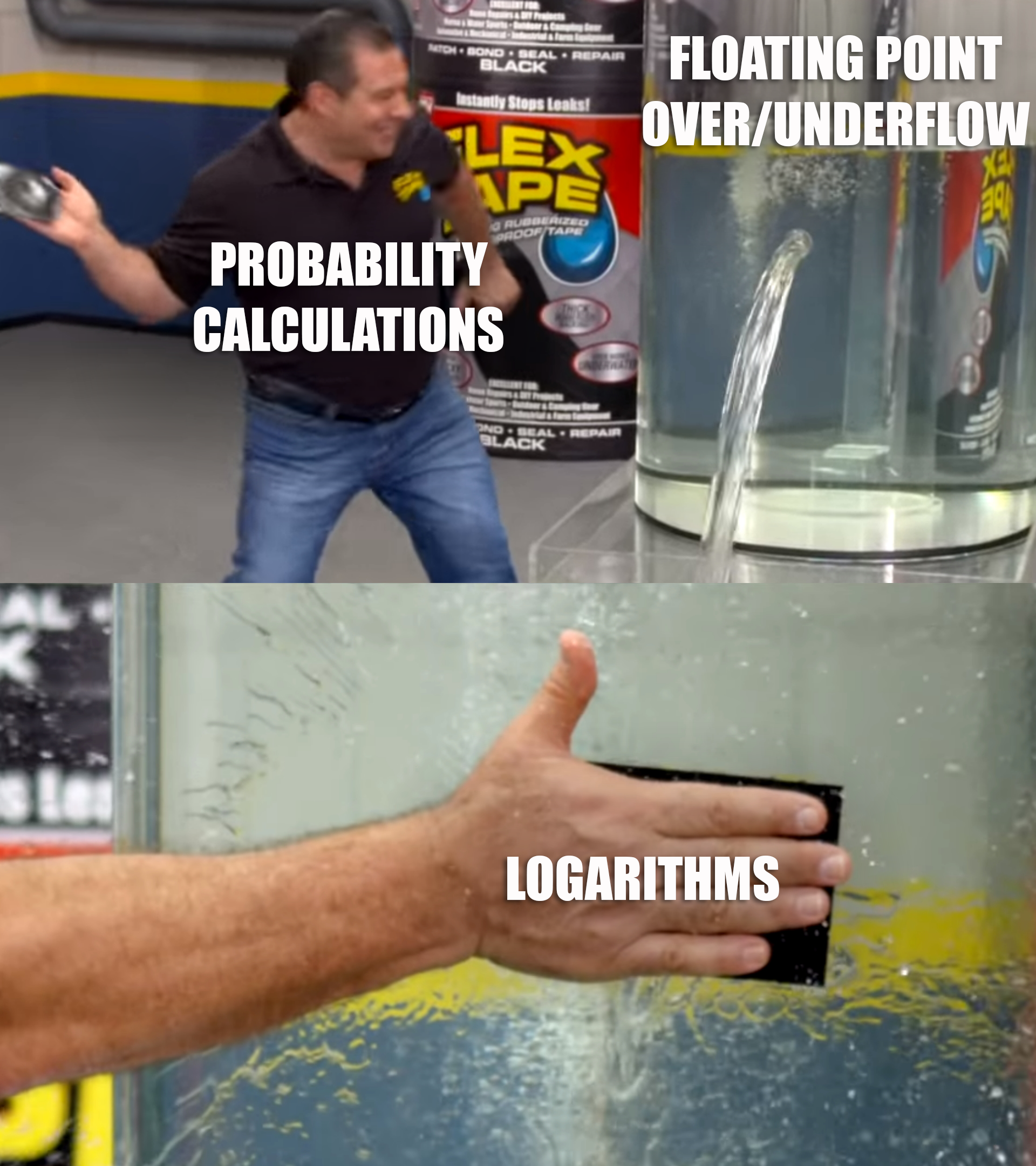

Dragons: Probability calculations tend to under- and overflow due to floating point precision.

Describing Uncertainty

Confidence Intervals

Frequentist estimates have confidence intervals, which will contain the “true” parameter value for \(\alpha\)% of data samples.

No guarantee that an individual CI contains the true value (with any “probability”)!

Example: 95% CIs for N(0.4, 2)

Code

# set up distribution

mean_true = 0.4

n_cis = 100 # number of CIs to compute

dist = Normal(mean_true, 2)

# use sample size of 100

samples = rand(dist, (100, n_cis))

# mapslices broadcasts over a matrix dimension, could also use a loop

sample_means = mapslices(mean, samples; dims=1)

sample_sd = mapslices(std, samples; dims=1)

mc_sd = 1.96 * sample_sd / sqrt(100)

mc_ci = zeros(n_cis, 2) # preallocate

for i = 1:n_cis

mc_ci[i, 1] = sample_means[i] - mc_sd[i]

mc_ci[i, 2] = sample_means[i] + mc_sd[i]

end

# find which CIs contain the true value

ci_true = (mc_ci[:, 1] .< mean_true) .&& (mc_ci[:, 2] .> mean_true)

# compute percentage of CIs which contain the true value

ci_frac1 = 100 * sum(ci_true) ./ n_cis

# plot CIs

p1 = plot([mc_ci[1, :]], [1, 1], linewidth=3, color=:deepskyblue, label="95% Confidence Interval", title="Sample Size 100", yticks=:false, legend=:false)

for i = 2:n_cis

if ci_true[i]

plot!(p1, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:deepskyblue, label=:false)

else

plot!(p1, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:red, label=:false)

end

end

vline!(p1, [mean_true], color=:black, linewidth=2, linestyle=:dash, label="True Value") # plot true value as a vertical line

xaxis!(p1, "Estimate")

plot!(p1, size=(500, 350)) # resize to fit slide

# use sample size of 1000

samples = rand(dist, (1000, n_cis))

# mapslices broadcasts over a matrix dimension, could also use a loop

sample_means = mapslices(mean, samples; dims=1)

sample_sd = mapslices(std, samples; dims=1)

mc_sd = 1.96 * sample_sd / sqrt(1000)

mc_ci = zeros(n_cis, 2) # preallocate

for i = 1:n_cis

mc_ci[i, 1] = sample_means[i] - mc_sd[i]

mc_ci[i, 2] = sample_means[i] + mc_sd[i]

end

# find which CIs contain the true value

ci_true = (mc_ci[:, 1] .< mean_true) .&& (mc_ci[:, 2] .> mean_true)

# compute percentage of CIs which contain the true value

ci_frac2 = 100 * sum(ci_true) ./ n_cis

# plot CIs

p2 = plot([mc_ci[1, :]], [1, 1], linewidth=3, color=:deepskyblue, label="95% Confidence Interval", title="Sample Size 1,000", yticks=:false, legend=:false)

for i = 2:n_cis

if ci_true[i]

plot!(p2, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:deepskyblue, label=:false)

else

plot!(p2, [mc_ci[i, :]], [i, i], linewidth=2, color=:red, label=:false)

end

end

vline!(p2, [mean_true], color=:black, linewidth=2, linestyle=:dash, label="True Value") # plot true value as a vertical line

xaxis!(p2, "Estimate")

plot!(p2, size=(500, 350)) # resize to fit slide

display(p1)

display(p2)95% of the CIs contain the true value (left) vs. 94% (right)

Predictive Intervals

Predictive intervals capture uncertainty in an estimand.

With what probability would I see a particular outcome in the future?

Often need to construct these using simulation.

Upcoming Schedule

Next Classes

Next Week: Probability Models for Data

Assessments

Homework 1 due next Friday (2/7).

Quiz: Due before next class.

Reading: Annotate/submit writing before next class, will reserve time for discussion.