Probability Models

Lecture 04

February 3, 2024

Review

Probability Fundamentals

- Bayesian vs. Frequentist Interpretations

- Distributions reflect assumptions on probability of data.

- Normal distributions: “least informative” distribution for a given mean/variance.

- Fit distributions by maximizing likelihood.

- Communicating uncertainty: confidence vs. predictive intervals.

Linear Regression

How Does River Flow Affect TDS?

Question: Does river flow affect the concentration of total dissolved solids?

Data: Cuyahoga River (1969 – 1973), from Helsel et al. (2020, Chapter 9).

How Does TDS Affect River Flow?

Question: Does river flow affect the concentration of total dissolved solids?

Model: \[D \rightarrow S \ {\color{purple}\leftarrow U}\] \[S = f(D, U)\]

Log-Linear Relationships

\[ \begin{align*} S &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 \log(D) + U\\ U &\sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2) \end{align*} \]

Likelihood

How do we find \(\beta_i\) and \(\sigma\)?

Likelihood of data to have come from distribution \(f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)\): \[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x}) = \underbrace{f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)}_{\text{PDF}}\]

Here the randomness comes from \(U\): \[S \sim \mathcal{N}(\beta_0 + \beta_1 \log(D), \sigma^2)\]

Maximizing Gaussian Likelihood ⇔ Least Squares

\[y_i \sim \mathcal{N}(F(x_i), \sigma^2)\]

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{y}; F) = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp(-\frac{y_i - F(x_i)^2}{2\sigma^2})\]

\[\log \mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{y}; F) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(y_i - F(x_i))^2 \right]\]

\[ \begin{align} \log \mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{y}, F) &= \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(y_i - F(x_i)) ^2 \right] \\ &= n \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - F(x_i))^2 \end{align} \]

Ignoring constants (including \(\sigma\)):

\[\log \mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{y}, F) \propto -\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - F(x_i))^2.\]

Maximizing \(f(x)\) is equivalent to minimizing \(-f(x)\):

\[ -\log \mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{y}, F) \propto \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - F(x_i))^2 = \text{MSE} \]

But note: Don’t get an estimate of \(\sigma^2\) directly through least squares.

Back to the Problem…

# tds_riverflow_loglik: function to compute the log-likelihood for the tds model

# θ: vector of model parameters (coefficients β₀ and β₁ and stdev σ)

# tds, flow: vectors of data

function tds_riverflow_loglik(θ, tds, flow)

β₀, β₁, σ = θ # unpack parameter vector

μ = β₀ .+ β₁ * log.(flow) # find mean

ll = sum(logpdf.(Normal.(μ, σ), tds)) # compute log-likelihood

return ll

end

lb = [0.0, -1000.0, 1.0]

ub = [1000.0, 1000.0, 100.0]

θ₀ = [500.0, 0.0, 50.0]

optim_out = Optim.optimize(θ -> -tds_riverflow_loglik(θ, tds.tds_mgL, tds.discharge_cms), lb, ub, θ₀)

θ_mle = round.(optim_out.minimizer; digits=0)

@show θ_mle;θ_mle = [610.0, -112.0, 72.0]Maximum Likelihood Results

# simulate 10,000 predictions

x = 1:0.1:60

μ = θ_mle[1] .+ θ_mle[2] * log.(x)

y_pred = zeros(length(x), 10_000)

for i = 1:length(x)

y_pred[i, :] = rand(Normal(μ[i], θ_mle[3]), 10_000)

end

# take quantiles to find prediction intervals

y_q = mapslices(v -> quantile(v, [0.05, 0.5, 0.95]), y_pred; dims=2)

plot(p1,

x,

y_q[:, 2],

ribbon = (y_q[:, 2] - y_q[:, 1], y_q[:, 3] - y_q[:, 2]),

linewidth=3,

fillalpha=0.2,

label="Best Fit",

size=(600, 550))Residual Analysis

More General Models

Structure of a Probability Model

Unpacking linear regression:

\[\begin{align*} y_i &\sim N(\mu_i, \sigma^2) \\ \mu_i &= \sum_j \beta_j x^j_i \end{align*} \]

Note: Can handle heteroskedastic errors with a regression \[\sigma_i^2 = \sum_j \alpha_j z^j_i\]

Think Generatively

Components of probability model for observations:

- Model for “system state” (LR: \(\sum_j \beta_j x^j_i\))

- Choice of “error” distribution (LR: \(N(0, \sigma^2)\))

Source: Richard McElreath

You Can Always Fit Models…

But not all models are theoretically justifiable.

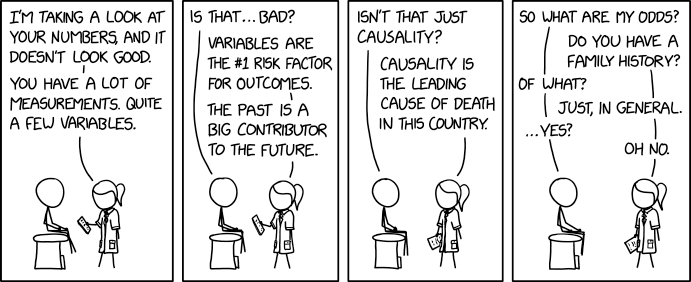

How Do We Choose What To Model?

XKCD 2620

Source: XKCD 2620

Example: Modeling Counts

What Distribution?

Count data can be modeled using a Poisson or negative binomial distribution.

Exploring the Data

- Mean: 3.3

- Variance: 135.4

Model Specification

We might hypothesize that more people fishing for more hours results in a greater chance of catching fish.

\[\begin{align*} y_i &\sim Poisson(\lambda_i) \\ f(\lambda_i) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P_i + \beta_2 H_i \end{align*} \]

\(\lambda_i\): positive “rate”

\(f(\cdot)\): maps positive reals (rate scale) to all reals (linear model scale)

Link Functions

\(\color{brown}f\) is the link function.

\(\color{royalblue}f^{-1}\) is the inverse link.

\[\begin{align*} y_i &\sim Poisson(\lambda_i) \\ {\color{brown}f}(\lambda_i) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 P_i + \beta_2 H_i \end{align*} \]

\[ \lambda_i = {\color{royalblue}f^{-1}}\left(\beta_0 + \beta_1 P_i + \beta_2 H_i\right) \]

Choosing a Link Function

Link functions are typically linked to distributions.

- Poisson models usually use the log link (positives → reals).

- Binomial/Bernoulli models use the logit link (\([0, 1]\) → reals) \[\text{logit}(p) = \log\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)\]

Fitting the Model

function fish_model(params, persons, hours, fish_caught)

β₀, β₁, β₂ = params

λ = exp.(β₀ .+ β₁ * persons + β₂ * hours)

loglik = sum(logpdf.(Poisson.(λ), fish_caught))

end

lb = [-100.0, -100.0, -100.0]

ub = [100.0, 100.0, 100.0]

init = [0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

optim_out = optimize(θ -> -fish_model(θ, fish.persons, fish.hours, fish.fish_caught), lb, ub, init)

θ_mle = optim_out.minimizer

@show round.(θ_mle; digits=1);round.(θ_mle; digits = 1) = [-1.5, 0.8, 0.0]Evaluating Model Fit

What Was The Problem?

- Model neglected other plausible contributors, e.g. live bait.

- Data is over-dispersed: higher variance than mean.

- Might be better described by a zero-inflated Poisson model:

- Visitors who spent little time are likely to catch no fish.

- Visitors who spent more time are likely to catch positive fish.

Key Points

Probability Models

- Think of regression as modeling system state (or expectation).

- Full probability model includes distribution of “errors” from expected state.

- Error models can be complex! More on this later…

- Generalized linear models may require a link to map regression to parameters.

- Fit models by maximizing likelihood: no problem using optimization routines.

Upcoming Schedule

Next Classes

Wednesday: Modeling Time Series

Next Week: Bayesian Statistics and Inference

Assessments

Homework 1 Due Friday (2/7).